At Via Castiglione I turn right and enter into the

fourteenth century world of the Pepoli family, Romeo and his son

Taddeo. They were rich bankers who, in the early thirteen hundreds,

controlled Bologna. At that time factions led by rich families often

fought each other for control of the city, so internal wars were common,

not only in Bologna, but in other Italian cities as well. The Pepoli

family belonged to the faction called the Scacchesi, from which the black

and white checkerboard derived on its heraldic shield (scacchi

refers to the game of chess). Their primary adversary was the Maltraversi

faction, when it wasn't the Roman Catholic Church or the Empire. The common

people would take sides and could, in fact, be very wishy-washy.

Bologna's independent nature got her into trouble with the church sometimes.

For instance, the General Council of the people gave unconditional power to

Taddeo Pepoli in 1337 and named him "Protector of the Peace and of

Justice" of Bologna. His constituted the first real signoria

(a governing body) in the city's history and a direct threat to the Roman

Catholic church's hegemony. Therefore, he had to deal immediately with

two interdicts by Pope Benedict XII placed on the city and the university,

for the city's presumptuous behavior. The interdicts would have threatened

the economic and diplomatic position of Bologna. Whether the Bolognesi

liked it or not, they were still subjects of the church in Rome.

So instead, Taddeo Pepoli became Captain of the People and Vicar of

the Church in Bologna, and his reign was one of peace between factions

in the city, with notable diplomatic achievements in the political arena

in northern Italy. He died of the plague in 1347, not rousted from

power by warring factions, as was the usual case.

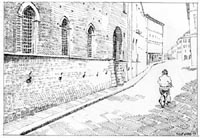

The fortress-like palazzo of the Pepoli family eventually took

up the entire block between Via Sampieri and Via dei Pepoli (n. 4 - 10).

The gothic Palazzetto Pepoli (n.4), built by Romeo and attributed to

Antonio di Vicenzo is the oldest construction. The giant portone

opens into a cavernous space, where my footsteps resonate off of the immense

stone walls and recall the shouts and vibrations of the past. Taddeo Pepoli

began his neighboring fortress in 1345 and today one can still note the

original door with its sculpted terracotta frame, and the black and white

chessboard squares referring to the family crest.

The modern world has encroached on that of the Middle Ages, of

course, so my imagination must come to the rescue as I push ahead on Via

Castiglione and remember the first time I noted the palazzo. I was puzzled

by the heavy iron serpent-like hooks and rings about five feet up from the

pavement on the street-side flank of the edifice. Via Castiglione was once

an open canal, one branch of the Torrente Savena that entered the city on

the left of Porta Castiglione. Legend says that the hooks and rings anchored

the boats that navigated the waterway that traveled from the south toward today's

Piazza Ravegnana. Bologna had been a city of canals.

The water from the Torrente Savena was initially directed into the city in

the twelfth century to fill the moat that circled the city outside the wall

of the Torresotti, offering protection from enemies and aiding in the functioning

of the flour mills in that part of the city. From the fifteenth century until

the mid-seventeenth century though, the water also became necessary for the

production of cloth and paper. Bologna's economy depended on the system of

canals.

Now, however, motociclette zoom by and their noise can make it

difficult to lose myself in the past. I visualize the narrow ancient

waterway as I look toward the south away from the city center, with

its particularly gentle bend off into the horizon. If I close my eyes

and listen, I can hear the slapping water and the dipping oars of the

boats that navigated the distances that big orange buses maneuver today.

I walk toward the intersection with Via Farina, cross it and then remember

the Ponte di Ferro, the iron bridge that once crossed the canal, as

I turn right onto the busy, modern street.

Under the wide porticoes amid the rush of pedestrians I

leave the Middle Ages and Taddeo Pepoli behind and glance into

the store windows. I enjoy window-shopping in Bologna, especially

the surprise when, as if by elfin magic, a black and white world

of skirts, blouses, sweaters and shoes can overnight become a domain

of soft yellow-green, vibrant orange and rich chestnut brown. Then

I have no choice but to pause for a moment and admire.

I continue on Via Farini, toward Piazza Calderini

and my mind slips back into medieval Bologna when this street

was known as Via dei Libri (of books) because the book trade

of the ancient university evolved here ("The University

of Bologna: Alma mater Studiorum").

When I arrive at Piazza Cavour, I turn left onto what

will become Via Garibaldi. A canopy of trees shelters the

quiet paths in the piazza to my left. Again I try to imagine

another Bologna and the street as it was known then, Via delle

Cassette di Sant'Andrea, where the law students used to attend

their lessons at the professors' quarters and, in fact, in public

places from Via D'Azeglio to today's Piazza Galvani.